What is liturgy? Simply put, a community coming together for a church service is known as a liturgy. However, the origin of the word liturgy –from a Greek word meaning public work or work for the public– hints at this concept’s deeper meaning.

So, what is the meaning of liturgy, then? The word that designates a common person who is not part of the clergy – laity – is derived from Greek. The word energy also originates from Greek. The roots of these two words combined form the original Greek word for liturgy: leitourgia. In a literal sense: energy for the people.

Within this broad framework of meaning, present-day pastors, church leaders, clergy, and parishioners are free to interpret the meaning of liturgy for themselves and their own community of worship. Among all Christians this usually includes communal elements of a celebration of Christ and our redemption, active participation, and the use of sacred words and actions.

Explore a Christian Ministry Degree – Request More Info Today!

Liturgy Had a Unique Significance for Early Christians

In addition to a modern understanding of community and a shared celebration in the light of Christ, liturgy has a long tradition that stretches back thousands of years. Its role as a marker of the passage of time was important in the early days of Christian history when things like clocks and calendars were rare.

In addition to a modern understanding of community and a shared celebration in the light of Christ, liturgy has a long tradition that stretches back thousands of years. Its role as a marker of the passage of time was important in the early days of Christian history when things like clocks and calendars were rare.

Keeping the Lord’s Day holy meant that every seventh day the faithful and their farm animals were required to rest and recuperate from their daily toil. In communities that were labor and agriculturally intensive this was important for health reasons, so much so that observing the Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments.

High illiteracy rates also meant that communal participation in the ritual of a church service held increased importance. Without being able to read the word of God and visualize His sacred text, participation in rituals like the procession, confession, litany, and communion were some of the most direct ways Christians could interact directly in their faith.

Today some churches adhere more strictly to a pattern of rituals and elaborate template for weekly worship than others. Churches that emphasize their pattern of worship may even refer to themselves as being a liturgical church, and churches with a less formalized service structure may declare themselves to be non-liturgical churches.

In these cases, the churches are using a definition of liturgy that’s synonymous with ritual. But in reality, any Christian faith community that joins together to praise God is engaged in liturgy: a church service and a public work.

What is the Liturgy of the Hours?

Also known as the Divine Office and Opus Dei, the Liturgy of the Hours is a Catholic tradition that refers to specific times of the day when select passages from the Bible –mostly psalms– and other religious content such as hymns and chants are presented aloud in church.

Also known as the Divine Office and Opus Dei, the Liturgy of the Hours is a Catholic tradition that refers to specific times of the day when select passages from the Bible –mostly psalms– and other religious content such as hymns and chants are presented aloud in church.

While Catholics in general are required to attend church on Sundays and holy days of obligation like Epiphany and All Saints’ Day, consecrated members of the church like priests and nuns are additionally required to attend the Liturgy of the Hours. Taking place seven times per day, attendance by lay churchgoers is encouraged though optional, and if it’s not possible to attend at a church people can pray independently.

The prayer times each day proceed in this order, and are referred to as the canonical hours:

- Matins – middle of the night

- Lauds – dawn, and considered one of the two main times of prayer

- Terce – “third hour” of the day (9 am)

- Sext – “sixth hour” of the day (noon)

- None – “ninth hour” of the day (3 pm)

- Vespers – evening, and considered the other main time of prayer

- Compline – just before bed

The Liturgy of the Hours as Outlined in a Special Breviary

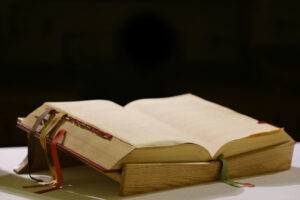

The material selected for each day and each canonical hour is determined in a book called a breviary. Historically there were many breviaries approved by the church, such as a Franciscan breviary for the Franciscans, an Ambrosian breviary for the Ambrosian Rite, and so on.

The material selected for each day and each canonical hour is determined in a book called a breviary. Historically there were many breviaries approved by the church, such as a Franciscan breviary for the Franciscans, an Ambrosian breviary for the Ambrosian Rite, and so on.

Following the Vatican Two Council between 1962 and 1965, the Catholic Church issued a revised breviary intended for all believers in four volumes titled, The Liturgy of the Hours, which is still considered the standard to this day, though religious groups are not required to use this specific breviary.

What is the Liturgy of the Word?

In Catholicism a church service is divided into five parts:

- Introduction

- Liturgy of the Word

- Liturgy of the Eucharist

- Communion

- Conclusion

The Liturgy of the Word represents Catholics coming together to celebrate the word of God as revealed through scripture. It’s made up of readings from the Bible, songs, and an interpretation of scripture by the priest. The readings and songs change throughout the year according to the Church calendar.

The Liturgy of the Word follows a specific format. At weekly mass on Sundays and on holy days of obligation this is:

- A reading from the Old Testament (or from the Acts of the Apostles during Easter season).

- In response to the reading a psalm is either read or sung.

- A reading from the New Testament – this is usually from a Letter of Paul (Pauline epistle), but can also be from another epistle, the Acts of the Apostles, or the Book of Revelation.

- At this point a gospel acclamation is typically sung, which is done in preparation to receive the word of God via the upcoming gospel reading.

- A reading from one of the New Testament Gospels –by Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John– which talks about their personal experience with Jesus.

- Following the gospel, the priest or deacon interprets its meaning in a homily or sermon.

The New Testament gospel reading is the high point of the Liturgy of the Word where the Catholic community feels the presence of Christ among them. Before the gospel is read the congregation makes the sign of the cross over their foreheads, lips, and heart. This symbolizes that the upcoming presentation of the gospel will be present in their thoughts, in their speech, and in their hearts.

After the gospel reading the priest or deacon attempts to connect the story just heard by the congregation with their daily lives in a way that’s relatable and understandable. This segment is called a homily if it ties in directly to the readings from the day’s Liturgy of the Word. If it’s on a different topic, like morality or beliefs, then it’s called a sermon.

What is the Liturgy of the Eucharist?

In Catholicism the Liturgy of the Eucharist is one of the five main segments of a mass.

In Catholicism the Liturgy of the Eucharist is one of the five main segments of a mass.

We’re familiar with the concept of Thanksgiving, a holiday we celebrate every year. So were the early Catholics, who used the Greek word “eucharist” –also meaning thanksgiving– to celebrate the life of Christ.

The Liturgy of the Eucharist is about giving thanks to God for sacrificing his only son to die for the sins of humanity and humanity’s redemption.

This is the part of the church service where Catholics prepare to symbolically join together with Jesus Christ by sharing in his bodily mortal sacrifice by breaking bread together, and being one in Christ’s love –his heart and blood– by sharing a drink of wine from a common chalice.

The Liturgy of the Eucharist follows a specific template:

- First the priest greets the congregation by saying, “the Lord be with you,” to which the congregation responds affirmatively.

- Next is the Eucharistic Prayer and Preface, which explain how praising God is right and just.

- This is followed by the Sanctus, which is a hymn giving thanks to the Lord.

- Then comes the Epiclesis, a word from Greek meaning “to call down,” or, “invocation.” This is said by the mass presider as he makes the sign of the cross over the bread and wine which are displayed on the alter, symbolizing the moment when the Holy Spirit embodies these metaphors which are to be shared in communion with the congregation.

- The Institutional Narrative follows this, during which the mass presider recalls the words of Jesus as he shared his last supper with his disciples.

- The final ritual is the Memorial Acclamation, where the mass presider proclaims the mystery of faith in God. This is followed by a singing or recitation of an acclimation that reminds the congregation of the shared sacrifice of Jesus.

- This is followed by an intercessory prayer, which reminds the congregation that their present situation is lacking compared to the glory of Heaven that awaits those who are called in the future.

- The Doxology represents the conclusion of the Eucharistic prayer where the primacy of God and the Holy Spirit are acknowledged as the presider raises the bread and chalice above the alter for all the congregation to witness.

- After the Doxology the congregation responds with “amen,” at which point Jesus’ symbolic body and blood –the blessed bread and wine– are prepared to be distributed in the next of the five main rituals: communion.

While it might seem that the prayers during the Liturgy of the Eucharist are the same each week, there are actually 13 different Eucharistic Prayers and 85 different prefaces that can be selected, which correspond to the church calendar.

The Liturgy of the Eucharist transforms ordinary bread and wine into the symbolic and real representations of Jesus’ body and blood. In so doing, the congregation is also symbolically transformed into Jesus’ disciples who shared in his bounty where no one knew hunger or thirst.